Yesterday And Today

All I Want for Christmas is THE BEATLES!!! or Art in the Slaughterhouse of Commerce

The Beatles “Mad Day Out” in London, July 28, 1968 (as seen in The Beatles 1962—1966 and The Beatles 1967—1970 LPs).

Yo! Ho! Ho! Friends and neighbors… Once again, it’s that time of year to personally and/or collectively reject or embrace the traditions of the holiday season. Call it Kwanzaa, Chanukah, ChristMass–we embody the mythologies and symbols that suit us. Thankfully, we’re free to celebrate the Solstice anyway we imagine. And personally, if there’s one thing that gets me in the seasonal spirit each and every December, it’s the annual ritual of listening to all seven of the Christmas messages that the Beatles recorded between 1963 and ‘69. Decades before the digital download, these messages were sent directly to members of the Beatles’ fan club via flexi-disc as a whimsical means of connecting with their constituency and exemplifying how much the 1950s BBC radio program The Goon Show (featuring Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers, and Harry Secombe) was an influence on their own irreverent, absurdist sense of humor.

The continued popularity of the San Diego Beatles Fair each spring over the last six years demonstrates that there remain two kinds of people in the world: those who have unconditionally taken the Fab Four to heart, and those who haven’t the ears to hear nor the soul to conceive of how mind-blowing the musical inventions are that the Beatles unleashed upon the world during their spectacular assent to our collective cultural summit. As Los Angeles DJ Jimmy O’Neill, the host of ABC-TV’s Shindig! proclaimed in October of 1964, the Beatles are indeed “the entertainment phenomenon of the century!” The Beatles undoubtedly belong to the 1960s. But their work and ideas have long since persevered outside their temporal milieu. They are, in a word, timeless.

At first glance, the Beatles’ meteoric rise in America might appear to be a classic “overnight success” story. But the truth of the matter is the Beatles spent a grueling eight or nine years plunking down their dues in dance halls, coffee bars, and strip joints, living out of a transit van, and sorting out the dubious machinations of show business. By the time Capitol Records in America embarked upon a media blitz of the first order in January 1964, the change in the culture was so swift that it appeared the Beatles had materialized out of nowhere. Which is exactly where their hometown of Liverpool, England, sat in the consciousness of the American teenager before the release of their fifth single, “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” went to number one for seven weeks on Billboard’s Hot 100 on February 1st. Eight days later, 73 million people would tune in for their historic debut on The Ed Sullivan Show, and forever afterwards, the Beatles and Liverpool would be synonymous.

There is many an American Beatles fan that grew up listening to the albums and singles issued by Capitol Records during the 1960s (and beyond) who still can’t wrap their heads around the original British configurations that were released by Parlophone in England. And yet, when the Beatles entire catalog of studio recordings was re-released on compact disc in 1986—87, it was (by and large) the British LPs that the group chose to make the worldwide standard of how to perceive and receive their art. As with most things in the world, context is crucial to a deeper understanding of history, and “reality” in general.

Prior to 1967, it was common practice in the music industry for British releases to be reconfigured for the American market. In nearly every instance the U.S. versions would feature different songs, photos, and liner notes. British LPs generally featured 14 songs per title, with both sides of a 45rpm single considered a distinct medium apart from LPs. In America the standard for an LP was usually 11 songs (or occasionally 12), and those configurations always included the same material released on 45s. These are two very different approaches to the same body of work, explaining how the British record buying public had 12 LPs to choose from, separate from songs available on EPs and singles, and the Americans had the same material spread across 20 LPs. Until the uniform worldwide release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in June of ‘67, every single LP released in America is a compilation created by third parties with no direct connection to the Beatles. As far as Capitol Records is concerned regarding the Beatles’ saga, they ought to be viewed as money-grubbing bastards whose primary concern was to bilk as much cash from their golden goose as possible, with little or no respect over how the Beatles’ art was presented to the American public.

While born in the very last year of the Baby Boom, I was only six when the Beatles officially disbanded in 1970. Everything I know about them is viewed through the kaleidoscopic prism of a rear-view mirror. Thanks to the influence of Top 40 radio, I spent my first few years as a consumer purchasing random 45s at the local Drug Fair in Arlington, Virginia, for 69 cents each, because the cost of an LP seemed daunting by comparison. But I finally worked up the nerve, and the first long-playing album that I forked over $9.98 of my own pocket money for was the epic 1973 compilation The Beatles 1967—1970, otherwise known as the “Blue Album,” the later-day counterpart to The Beatles 1962—1966 (aka the “Red Album”). These dual double LP sets were conceived by then-manager Allen Klein as a countermeasure against two pirated box sets being advertised on national television titled Alpha Omega. When I purchased the “Blue Album” at the age of ten, I was relatively oblivious to the Beatles’ backstory. But what I was soon marveling at was how every single song on this 28-track compilation was both familiar and a cosmic mystery, and I was gobsmacked by how much classic material was contained on these four sides. (Klein embarked on a similar re-packaging exercise with his former clients, the Rolling Stones, on Hot Rocks 1964—1971, and More Hot Rocks (Big Hits & Fazed Cookies).)

A few years later in June of ’76, Capitol issued the double LP concept album Rock ‘n’ Roll Music. Its detractors, which included John Lennon and Ringo Starr, criticized the cheesy ‘50s iconography of the packaging that attempted to cash in on the nostalgic buzz of American Graffiti and Happy Days–hence the images of fin-tailed cars, a Wurlitzer jukebox, hamburgers, glasses of Coca-Cola, and pin-ups of Marilyn Monroe. But as a collection of songs the selections and segues hold up remarkably well, emphasizing the R&B roots of the Beatles’ music. Whether or not by design, the album dovetailed rather nicely with the then-current Wings over America tour, and the number one LP Wings at the Speed of Sound, which kept the Rock ‘n’ Roll Music LP stuck at the number two position on the Billboard Hot 200 Album Chart. Initially, Capitol Records selected “Helter Skelter” as a single, but a recently aired made-for-TV movie of the same name about the Tate-LaBianca murders made that a rather dodgy choice, and “Got to Get You Into My Life” was chosen instead to promote Rock ‘n’ Roll Music. The single went all the way to number seven for three weeks in July/August of ’76.

Not yet being familiar with Revolver, where “Got to Get You Into My Life” originally appeared as an album track, it really messed with my 12-year-old mind how a song from 1966 could end up being a Top Ten chart hit ten years after it was initially released. The novelty song “Monster Mash,” by Bobby “Boris” Pickett and the Crypt-Kickers, enjoyed a similar fate when the number one smash from 1962 reached the Top Ten a second time in 1973. I was nonplussed at how Paul McCartney, who had just had a number one hit with “Silly Love Songs,” could also have a current hit single with his band from the previous decade. And the really weird thing was how contemporary the Beatles sounded on AM radio next to the likes of Elton John, Queen, Peter Frampton, Gary Wright, War, and the Brothers Johnson.

I scratched my head, I searched for clues, I read periodicals and poured over the scant information included on record sleeves. Within a few years I had amassed a number of other Beatles discs, but I still lacked the context of how these songs fit into the evolution of their career, and the culture of the Sixties in general. That’s the way it was in the pre-Internet days–you had to seek out grassroots information by word-of-mouth, by talking to other historians and collectors–you had to dig a little bit deeper at the local library. But a major turning point in my comprehension came when I received a copy of Harry Castleman and Walter J. Podrazik’s All Together Now–The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961—1975.

Despite the occasional error, Castleman and Podrazik’s extensive research was a godsend, and became the first of many reference sources towards understanding how the Beatles’ records were released out into the world. Eventually I read over a hundred books and periodicals on the subject, making it a personal mission to understand the chronological arc of how the Beatles’ art developed. Where did they come from? How did it all begin? Who was involved? Where are all the significant places that their odyssey touched upon along the way? Why and how did it come to an end? And what were the four individuals up to after their breakup?

As a child of the ‘70s, it was easy to know what the four individual Beatles were up to because you were still hearing them produce new music on the radio. All four of the Beatles enjoyed number one records as solo artists, and until the assassination of John Lennon on December 8, 1980, the question on every journalist’s lips whenever they had access to a Beatle was whether or not they would ever play together again. Lennon’s murder effectively shut down all future inquiries. And, yet, somehow they did manage to reunite in the studio in 1995….

***

Yes, there are hundreds of books available on every aspect of Beatles minutiae, but the first place any enthusiast should begin to broaden their understanding of this emotional roller coaster ride is the superlative tome by the late, great Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. Initially published in 1994 and fully revised in a superior edition in 1997, no one has written a more lyrical book deconstructing the musical trajectory of the Beatles’ landscape than MacDonald. Revolution in the Head has the ring of true poetry while explaining and contextualizing why a piece of music or a performance is extraordinary. MacDonald’s observations inspire wonderment and have you scrambling for the turntable to investigate this or that claim or revelation. Conversely, he can also explain with equal aplomb why a piece of music doesn’t work. You won’t always agree with his point of view, but if you only own one book on the Beatles–this is it.

However, if you’re looking for a comprehensive nuts and bolts accounting of the Beatles’ career in the studio, on stage, and in the media, the undisputed king of chroniclers is Mark Lewisohn. While his prose can be rather dry, he more than makes up for it with the type of exclusive access he has to EMI’s archives, and his tireless attention to detail, piecing together the insane intensity of the Beatles’ day-to-day activities. To that end, The Complete Beatles Chronicle and The Beatles Recording Sessions are also essential volumes for your bookshelf. Various biographies, tell-all memoirs, scrapbook compendiums, and opportunistic tie-ins should be approached with caveat emptor in mind.

Throughout the 1980s a plethora of bootleg recordings and video clips began to circulate amongst the faithful, and you can drive yourself to ill health and financial ruin attempting to collect even a fraction of what is out there. That said, there is much to be learned about the Beatles’ evolutionary process by checking out such titles as the Unsurpassed Masters series, The Decca Tapes, Back-Track, Sessions, It’s Not Too Bad (The Evolution of Strawberry Fields Forever), and Turn Me On Dead Man: The John Barrett Tapes. But the ability to understand the Beatles’ career increased exponentially with the release in 1995—96 of the Anthology project: simultaneously a television documentary series, a three-volume set of triple albums, and a hardcover coffee table book documenting the authorized history of the band.

Anthology focuses on unreleased performances and outtakes presented in roughly chronological order, along with two new songs based on demos recorded by Lennon in the 1970s: “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love,” both produced by Electric Light Orchestra mastermind and Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne. In spite of being somewhat sanitized and occasionally contradictory, the Anthology documentary (significantly expanded for the home video version) is of supreme importance in understanding the Beatles’ legacy. Words can be wonderful, but to see and hear the Beatles with the reaction they provoked from their audiences remains a singular occurrence in the history of popular culture. To that end, another priceless document is the Maysles brothers film The First U.S. Visit, which is the cinéma vérité template for Richard Lester’s 1964 masterpiece A Hard Day’s Night.

***

As a professional archivist I have explored the Beatles’ recordings with an obsessive zeal, and to a large extent still do. Before the advent of the compact disc I would compile cassette tapes in chronological order of how the Beatles’ career evolved, mindful of how one recording session led to another, and how those recordings were selected, mixed down, and assembled for release on 12-inch or 7-inch discs. I came to understand the peculiar way the Beatles were marketed in America as opposed to their native Britain, and it was tricky figuring out how to obtain a complete collection of their studio recordings. But by picking up various titles from both sides of the pond, I managed to piece together the Beatles story. Here is how it lays out from Britain to the U.S.A.

Aside from the recordings made with Tony Sheridan in Hamburg, Germany in 1961, the first record to bear the Beatles’ name came out in October of 1962: “Love Me Do” backed with “P.S. I Love You.” It reached number 17 in the U.K. and was not released at the time in America. When their second single, “Please Please Me” b/w “Ask Me Why” reached the number one spot in the U.K., the obvious thing to do was to capitalize on their momentum with a full-length LP. In addition to the four aforementioned titles, the Beatles recorded all ten of the other tracks on their long-playing debut Please Please Me in one day, on February 11, 1963. This is nothing short of miraculous. Upon its release in March, the LP immediately shot to number one in the U.K.

A third single was released in April, “From Me to You” b/w “Thank You Girl,” and a fourth in August, “She Loves You” b/w “I’ll Get You.” Both of these also went straight to number one in the U.K. Soon, the newspapers had invented a term for all the hysteria being showered upon the group and their music: “Beatlemania.” Yet for all their success in Great Britain, none of their records had made the slightest dent in the U.S. charts.

As the Beatles’ producer George Martin explains in the Anthology series: “We were trying to get into America all the time. I really thought ‘She Loves You’ would have broken them in America. If you think of our frustration here, we were being turned down by the company [Capitol Records] which EMI actually owned. And I was so frustrated by this, I said ‘Well, if they’re not going to put it out–in the case of ‘From Me to You’ being the first one we offered them–they can’t deny us other people putting them out.’ So, I would take the record back from them and try and get it out with another label. And I did negotiations with Swan and Vee-Jay, each of whom are tiny labels in the States, who took one or the other titles. And they put those records out in America. And, of course, being a small label, they didn’t make a great deal of success.”

Paul McCartney: “And that was the way it worked out. We released ‘Please Please Me’–flop. ‘From Me to You’–flop. Changed record labels, released ‘She Loves You’–flop. They had all been big records in England, all of them number one. And all of them, flops. Nothing.”

George Martin: “But by [the end of 1963] the news from England and Europe was overwhelming. They were a hit group and Capitol Records had to take them more seriously than they’d done before. And also, the Swan and Vee-Jay labels were making inroads–they were selling by this time. So Capitol was forced to release ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand.’ It wasn’t designed specifically for the American market, but like the ones before it, it was a great record.”

By November of ’63, the Beatles had recorded a second 14-song LP, With the Beatles, that like it’s debut evenly split the selections between carefully chosen covers from their stage repertoire and original compositions from the songwriting partnership of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Regarding the song “Misery,” Ian MacDonald observes: “With this song Lennon and McCartney achieved eight writing credits for the Beatles first LP–an unprecedented achievement for a pop act in 1963. For an artist to write anything at all in those days of dependence upon professional songwriters was considered positively eccentric. Even vaunted originals like Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and Roy Orbison looked to other songwriters to help them out. The sudden arrival of a group which wrote most of its own material was a small revolution in itself, and it is a recurring testimony of later songwriters that it was the do-it-yourself example of the Beatles which impelled them to form bands of their own.”

As Martin states above, the singles released by Vee-Jay and Swan made little impact in the U.S. But when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” b/w “This Boy” was released in the U.K., the Beatles fortunes’ in America changed overnight.

Much has been speculated that the assassination of U.S president John F. Kennedy led to the manic outpouring of emotion heaped upon the Beatles arrival, as America’s youth somehow needed a distraction and a release from its emotional grieving. Armchair analysis aside, the fact remains that these were and are exciting records, and they duly capture the zeitgeist of their times. And as Capitol Records finally decided to get into the game in the first weeks of 1964, the story gets muddy.

Capitol issued “I Want to Hold Your Hand” b/w “I Saw Her Standing There” at the end of 1963, and three weeks later issued Meet the Beatles!, with the cover proclaiming to be “The First Album by England’s Phenomenal Pop Combo.” But that’s not true. Yes, it’s the first LP Capitol released in America, but rival label Vee-Jay out of Chicago had already released a version of Introducing…the Beatles the previous July, with a temporary license to issue 16 of the Beatles’ masters before Capitol understood what a hot property they had on their hands. Legal maneuvers went back and forth until Capitol conceded that Vee-Jay (and its subsidiary Tollie Records) could issue Beatles product in America until October of ’64. Vee-Jay issued four LP albums, four singles, and an EP out of the 16 tracks it controlled from its 1963—64 license period. Those 16 tracks are the songs found on the British Please Please Me LP and both sides of the “From Me to You” single.

When Capitol compiled Meet the Beatles! it took its 12 songs from three sources: “I Saw Her Standing There” from Please Please Me, both sides of the “I Want to Hold Your Hand” single, and nine tracks (featuring all eight original compositions) from With the Beatles.

In the second week of March ’64 both Parlophone and Capitol released the Beatles’ sixth single, “Can’t Buy Me Love” b/w “You Can’t Do That.” Less than a month later Capitol issued The Beatles’ Second Album (really their third American LP), featuring the five remaining tracks from With the Beatles (all of them cover songs), the b-side of “Can’t Buy Me Love,” both sides of the “She Loves You” single, and two tracks from the yet-to-be-released British EP Long Tall Sally. You really need a scorecard to keep up.

In June of ’64 Parlophone issued the Long Tall Sally EP in Britain, a unique configuration not issued elsewhere, containing “Long Tall Sally,” “I Call Your Name,” “Slow Down,” and “Matchbox.” A month later in July, Parlophone issued the third British Beatles LP A Hard Day’s Night. All seven songs from the film’s soundtrack are featured on side one, with six more tracks on side two. This album is unique for many reasons, least of all being the only album in the Beatles’ catalog that exclusively features Lennon/McCartney originals.

As part of the arrangement to produce their first feature film, United Artists was allowed to release on their own imprint the soundtrack to A Hard Day’s Night in America, featuring all seven songs from the film, “I’ll Cry Instead,” and four pieces of incidental music recorded under the musical direction of George Martin. But that certainly didn’t stop Capitol from reissuing five of the A Hard Day’s Night songs on their Something New configuration a month later. Adding three songs from side two of the British A Hard Day’s Night, they took the remaining two tracks from the Long Tall Sally EP, and rounded out this hodgepodge with the German re-recording of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” (“Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand”).

In November of ’64, Capitol continued to cash in with The Beatles’ Story, a largely forgettable attempt at mythologizing the Beatles’ brief history for an adolescent audience. November/December also saw the release of the Beatles’ eighth British single “I Feel Fine” b/w “She’s a Woman,” as well as their fourth LP Beatles for Sale. Capitol managed to squeeze two LPs out of these tracks, starting with Beatles ’65, utilizing eight songs from Beatles for Sale, “I’ll Be Back” from the British A Hard Day’s Night, and both sides of the “I Feel Fine” single.

In March of ’65, Capitol finally issued 11 of the 14 Please Please Me tracks that had previously been released by Vee-Jay, calling their version The Early Beatles. Although “I Saw Her Standing There” had already been released on Meet the Beatles!, for some reason Capitol neglected to release the outstanding originals “Misery” and “There’s a Place” at this time, and these two songs would not make their Capitol debut until 1980 on the U.S. Rarities LP. This is a ridiculous oversight, particularly as they were scraping the bottom of the barrel to locate source material (i.e., “Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand”).

April of ’65 saw the release of the Beatles’ ninth British single “Ticket to Ride” b/w “Yes It Is.” The single was a preview for the upcoming second feature film that at this point was called Eight Arms to Hold You, but by the time the film was finished in July, had wisely been re-titled Help! However, before the soundtrack to Help! was issued in August, Capitol released Beatles VI in June, another mishmash of material sourced from Beatles for Sale (six songs), the b-side of “Ticket to Ride,” three songs from side two of the upcoming British Help! LP, and one song specifically recorded to round out this compilation, a cover of Larry Williams’ “Bad Boy.” On the cover of Beatles VI the Beatles are all seen collectively with a knife in their hands. You could consider this exhibit ‘A’ for anyone looking for clues (real or imagined) about how Capitol was chopping up their artistic output.

Tied-in with the release of the Beatles’ second feature film is their tenth British single “Help!” b/w “I’m Down.” A fortnight later the British Help! LP was released, configured just like A Hard Day’s Night, with seven originals from the film on side one and seven additional recordings on side two. The American Help! LP was configured just like the United Artists version of A Hard Day’s Night: seven tracks from the film’s soundtrack augmented by five tracks of incidental music, again provided by George Martin and orchestra.

Before 1965 was over the Beatles would record what is arguably their finest record, their sixth British long-player Rubber Soul. Released concurrently at the beginning of December with the double A-sided single of “We Can Work It Out” and “Day Tripper,” Rubber Soul demonstrates a significant leap forward in maturity and innovation, partially due to the creeping influence that the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, and psychotropic substances were asserting upon the group. The original 14-track British LP displays a sublime synergy–a perfect distillation of the Beatles’ artistic intentions. Yet Capitol in America, in an attempt to create the illusion that this was somehow the Beatles’ “folk rock” LP, drastically changed the mood and the feel of the album. Capitol pulled four songs from the British configuration (“Drive My Car,” “Nowhere Man,” “What Goes On,” and “If I Needed Someone”) and substituted two acoustic numbers from the second side of the British Help! LP (“I’ve Just Seen a Face” and “It’s Only Love”), creating a very different listening experience. It’s open to debate about which version is preferable, and this is the one instance in Capitol’s meddlesome attitude with the Beatles’ catalog where the tinkering is not a total disaster. But my feelings regarding Rubber Soul probably have as much to do with being indoctrinated with the Capitol version since the age of ten as much as anything else. I remain a staunch defender of the Beatles’ creative output as it was intended. And yet, the American Rubber Soul is not without its charms (love that false start on “I’m Looking Through You”).

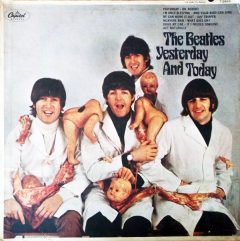

However, the next two releases by Capitol in the first half of 1966 clearly demonstrate how “out to lunch” their creative decisions could be in order to create product. At the end of June, Capitol released the LP Yesterday and Today, utilizing the four British Rubber Soul tracks that had been set aside, plus the “We Can Work It Out”/”Day Tripper” single, as well as “Yesterday” and “Act Naturally,” from the British Help! LP. But what is particularly galling is, in order to create the 11-song Yesterday and Today, Capitol pulled three key John Lennon songs off the forthcoming Revolver (“I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Dr. Robert”), destroying the mystical perfection of the 14-track original, just to crank out another piece of American product. It’s akin to needlessly chopping off the arms of a Da Vinci, for chrissakes. Capitol could have just as easily taken “I’m Down,” and the forthcoming single of “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” (my all-time favorite Beatles track btw), and put those songs on Yesterday and Today, leaving Revolver in its pristine state. Instead, Capitol released Revolver in America with only 11 tracks–a very different experience without those three Lennon songs. But artistic integrity has never been a part of Capitol’s modus operandi. And this is where we get to a crossroads of sorts in the Capitol Records saga of the Beatles’ LPs.

It’s difficult to verify what the Beatles’ intentions were when they embarked upon a photo shoot with photographer Robert Whitaker, where they donned white smocks and allowed themselves to be draped in pieces of raw meat with decapitated baby doll parts strew about. One school of thought regarding Yesterday and Today’s “Butcher Cover” (as it came to be known) is that this was a form of protest against the Vietnam War. Others believe that it is a direct commentary about how their artistic output had been “butchered” for the North American market. Whatever the motivation, the outcry against the image in America led to most of the original Yesterday and Today albums being recalled, with an innocuous picture of the Fabs around a steamer trunk pasted over the offending image. This face-saving maneuver by Capitol led to a $250,000 debacle, and created of one of the most sought-after items in the history of record collecting. Depending upon the “state” of the album and overall condition, copies of the original “Butcher Cover” change hands for hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of dollars.

By August of ‘66 the Beatles had sworn off touring after three years of performing to a wall of white noise. After incidents of police brutality in the Philippines and skirmishes in the U.S. over Lennon’s comments in the British press about how “we’re more popular than Jesus now,” the Beatles took a well-deserved break, with Lennon acting in Richard Lester’s How I Won the War, McCartney composing a film score for The Family Way, Harrison visiting India to study Hindu culture and music, and Starr “pottering about in Surrey.”

It was nearly six months before the group was heard from, with rumors of a breakup squashed when the Beatles released what is arguably the greatest double-sided single in the history of popular music: “Strawberry Fields Forever” coupled with “Penny Lane.” Their 14th British single from February of ’67 is truly unique, a groundbreaking achievement unlike anything that has been heard before or since. Once again I refer you to MacDonald’s Revolution in the Head: “Anyone unlucky enough not to have been aged between 14 and 30 during 1966—7 will never know the excitement of those years in popular culture. A sunny optimism permeated everything and possibilities seemed limitless. Bestriding a British scene that embraced music, poetry, fashion, and film, and in which English football had recently beaten the world, the Beatles were at their peak and looked up to in awe as arbiters of a positive new age in which the dead customs of the older generation would be refreshed and remade through the creative energy of the classless young. With its vision of ‘blue suburban skies’ and boundlessly confident vigour, ‘Penny Lane’ distills the spirit of that time more perfectly than any other creative product of the mid-Sixties. Couched in the primary colours of a picture book, yet observed with the slyness of a gang of kids straggling home from school, ‘Penny Lane’ is both naïve and knowing–but above all thrilled to be alive.”

Having decided with Rubber Soul and Revolver that the studio was now their canvas, and unburdened by the task of reproducing their work on stage, the Beatles worked for the next four months on what is largely considered their magnum opus: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Beatles insisted that this album be released worldwide in the exact same format, with Capitol finally acceding to their wishes. Love it or not, Sgt. Pepper’s is a complete work that cannot and should not be dismantled. But then again, I happen to feel that is the case with all seven of the British LPs that preceded Sgt. Pepper’s…but what do I know? Perhaps I’m too much of a purist?

A month after the release of Sgt. Pepper’s, the Beatles appeared on the first worldwide satellite linkup ever produced for television. Representing Britain on the Our World program, John Lennon composed the universal anthem of the summer of ’67: “All You Need Is Love.” Released as a single with “Baby, You’re a Rich Man” on the b-side, the single went straight to number one, and was the last record the Beatles released before the accidental overdose of manager Brian Epstein on August 27, 1967, at the age of 32.

The first project the Beatles embarked upon after Epstein’s death was the stupendous do-it-yourself folly of the Magical Mystery Tour film. As an early example of the MTV-styled promotional video, it is a fabulous time capsule. But the psychedelic fantasy sequences linking the songs together are stream-of-consciousness self-indulgence at its finest. Luckily, their music was still hovering at the top of the First Division as their 16th British single was unleashed in November: “Hello Goodbye” b/w “I Am the Walrus.” When Parlophone released the six songs from the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack in December they decided to split them up across two 7-inch EPs. Extended Play discs are a format that never really took off in America, and for once Capitol’s reliance on compiling the Beatles’ British output resulted in a lucky stroke of quintessence. Utilizing the 11-track format for the last time, Capitol put the six songs from the soundtrack on side one, and for side two combined the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane” single with “All You Need Is Love,” “Baby, You’re a Rich Man,” and “Hello Goodbye.” And voila! you have the American Magical Mystery Tour LP, which in subsequent decades became the worldwide context of how these songs are heard.

For the last two years of the Beatles’ career, their singles and LPs were released identically in both the U.K. and the U.S. March of ’68 saw the release of their 17th British single “Lady Madonna” b/w “The Inner Light,” the first time a George Harrison composition appeared on a 45rpm disc. On August 26th, 1968, “Hey Jude” b/w “Revolution” hit the shops, the first release through their newly formed company Apple Records, and the longest song to that point to ever top the charts at seven minutes and 11 seconds. It spent nine weeks at number one in the U.S., the longest run of any Beatles single. (Incidentally, for the trainspotters among you, with the advent of the Apple Records the A-side of a respective single would feature a Granny Smith apple and the b-side would feature the same apple split in half.)

As McCartney was composing his ode to Lennon’s son Julian about the breakup of his parent’s marriage (“Hey Jude” was originally “Hey Jules”), Lennon and Yoko Ono had fallen in love and become inseparable, and the Beatles’ inner-group relations were dipping to an all-time low. Just in time for Christmas, the double LP “White Album” The Beatles (the most ironic title in their history, considering it was the least group-like effort in their catalog) was completed, with minimal involvement from producer George Martin. Considering what else was going on in the world, 1968 turned out to be one of the most fractious, violent years of the modern era, with The Beatles an all too apt soundtrack for that peculiar season.

Two months after the “White Album” the Beatles were required to deliver another soundtrack album for their fourth film, Yellow Submarine. Aside from appearing on camera for barely a minute towards the end of the film, the Beatles had very little involvement with this animated psychedelic period piece. Essential for completists only, the soundtrack is a bit of a slight affair, offering up only four new Beatles songs. In addition to the title track from Revolver and “All You Need Is Love,” the album features two 1967 George Harrison compositions that were previously left in the can (“It’s All Too Much” and “Only a Northern Song”), and the fun, but banal McCartney nursery rhyme/singalong “All Together Now.” Only Lennon’s rollicking “Hey Bulldog” provides the album with any true momentum and excitement, and it sounds particularly fabulous in the sequencing of the aforementioned Rock ‘n’ Roll Music compilation. As with the American soundtracks for A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, the second side of the album is filled with incidental music composed and orchestrated by George Martin.

Without the guiding hand of Epstein to protect them from the viper’s nest of lawyers and businessmen that enveloped the group, the Beatles were artistically and financially floundering at the beginning of 1969. McCartney famously stepped into the breach by suggesting the Get Back project, a back-to-basics, let’s-all-play-live-again-in-the-same-room concept that was intended to inspire solidarity. Unfortunately, the exercise only served to alienate them further from one another, and the time they spent rehearsing and attempting to work up new material during January of ’69 turned out to be the best documented month of the group’s history, as well as the least pleasant. On January 30, 1969, along with guest keyboardist Billy Preston, the Beatles performed an impromptu concert on the rooftop of the Apple offices at 3 Savile Row in London, giving their final public performance to a surprised crowd of lunchtime office workers. After performing for a total of 42 minutes, the Metropolitan Police insisted that they cease and desist. Much of the footage from the rooftop concert can be seen in the 1970 feature film Let It Be, which at the time of this writing is still not officially available on home video.

The first evidence of the Get Back sessions came with the release in April of the Beatles’ 19th British single “Get Back” b/w “Don’t Let Me Down.” What is particularly telling about this single is it is the first record released by the group that does not feature a “Produced by George Martin” credit on the label (there is no production credit). It is also the first single since the days of Tony Sheridan where the Beatles share billing with an outside musician, in this case Billy Preston.

A mere six weeks after the release of “Get Back” came the group’s 20th British single: “The Ballad of John and Yoko” b/w “Old Brown Shoe.” The autobiographical nature of the A-side, along with a picture of the four Beatles and Yoko Ono on the sleeve, is a telling postcard/snapshot of a band in transitional disarray. What is weirdly wonderful about “The Ballad of John and Yoko” is the fact that Lennon and McCartney are the only two musicians performing on the track. With Harrison unavailable (or perhaps slighted) and Starr busy filming The Magic Christian, Lennon was chomping at the bit to get this song out to the public. Featuring McCartney on drums, maracas, bass, piano, and harmony vocals, and Lennon on lead and rhythm guitars and lead vocal, the track is a magnificent testimony to how deep the partnership between these two geniuses runs, which is even more bittersweet considering the acrimonious legal maneuvers that would occupy much of the following year.

With “Old Brown Shoe,” George Harrison places a second composition on a Beatles’ single, and it is a tour de force, demonstrating that the Beatles were, in the final analysis, a four-headed hydra that (when they wanted to) could outshine any other group of musicians in terms of soul and unity. This could have easily ended up a Harrison solo record, but in tandem with the other three Beatles, “Old Brown Shoe” sails into the stratosphere.

What is most miraculous in the third act of the Beatles’ narrative is that after the difficulty of The Beatles, and the debacle of the Get Back project, they were able to put their differences aside for a few months in the summer/autumn of ’69 and enlist producer George Martin to once more produce a unified work of balance, cooperation, and maturity. At the end of September ’69 the Beatles released their final recording together, Abbey Road, and with a coda of “and in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make” they must have known that this was destined to be their last trip together on the merry-go-round. With the release of their 21st British single, “Something” b/w “Come Together,” George Harrison was finally awarded his first and only A-side in the Beatles cannon of singles, having contributed two world-class songs to Abbey Road, along with “Here Comes the Sun.”

The remainder of ‘69 and the first half of 1970 was filled with both Lennon and McCartney getting married, the release of the U.S. only The Beatles Again compilation (aka Hey Jude), various solo projects, and the internecine bickering around who was going to guide Apple Corps. After McCartney married New York photographer Linda Eastman on March 12, 1969, he pushed for his new in-laws, the Eastmans, to look after the Beatles’ financial affairs. However, he was vetoed by the other three Beatles, and New York wheeler-dealer Allen Klein was brought in to look after Apple. A week after the McCartney nuptials, Lennon and avant-garde artist Yoko Ono were married (March 20) in “Gibraltar, near Spain.” Clearly, it was the end of an era.

There are any number of factors that led to the Beatles’ demise (Lennon’s drug induced apathy and the arrival of Yoko Ono, Harrison’s prolonged resentment at being considered a “junior partner” by both McCartney and Lennon, etc.), but the fact is they had grown apart, and it was much more pleasant to pursue solo projects than to deal with the politics of being a Beatle. Their last official recording session took place on January 3—4, 1970, when Harrison, McCartney, and Starr found it necessary to track a proper version of Harrison’s “I Me Mine” for the impending Let It Be album (Lennon was on holiday in Denmark). The penultimate album of the Beatles’ core catalog in terms of creation, the Get Back project crashed, burned, and mutated into the final Beatles album–it serves as the soundtrack to their fifth and final feature film, Let It Be. The 22nd British Beatles single “Let It Be” b/w “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)” was released in March 1970, in a different version heard on the LP. The b-side of “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)” has a rather curious history, being recorded during the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions, and features a bit of saxophone by the late Rolling Stone Brian Jones. Along with their fan club Christmas messages, this recording is as beautiful a peek into the Beatles Goon-style sense of humor as anything else they ever created. It’s nice to see that they ended this particular part of the journey on a whimsical note, for it serves as a far more pleasant dénouement to their story than the melancholic, superfluous U.S. single release of “The Long and Winding Road” b/w “For You Blue.”

***

There are scores of significant recordings released by the Beatles after 1970: the aforementioned Anthology series, Live at the BBC Volume One and Two, The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl, Let it Be…Naked, the Yellow Submarine Songtrack, Rarities, 1+, The Four Complete Historic Ed Sullivan Shows, and the mashup exercise/soundtrack to the Cirque du Soleil production of LOVE. There are also the multi-disc explorations of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and a brand new box set deconstructing The Beatles. When the Beatles’ core catalog was released on compact disc in 1986—87, and again remastered in 2009, the two volumes of the Past Masters series collected all of the tracks from various singles and EPs not found on the 12 British albums or the U.S. Magical Mystery Tour compilation. It sure is a lot easier in the digital age to track down all of the Beatles’ recordings than it was in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. However, if given the choice, I’d much rather listen to these performances in glorious analog sound (i.e., vinyl) on a decent hi-fi system. And fortunately, in 2018, you can do both.

The Beatles have become so ubiquitous in the last 55 years as to almost be taken for granted. In addition to touring the world several times over and performing on radio and television, they created their entire body of work in less than seven years. That is a staggering achievement no matter how you quantify it, and their example will remain the standard that all other groups are measured against for as long as we have that thing we call “rock ‘n’ roll.” Every single group that has come down the pike since the Beatles’ inception owes them a debt of gratitude. Without the Beatles, there is so much richness that would be missing from our lives in the 21st century, not the least of which is that giddy sensation that it’s great to be alive, and a thrill to be sharing all of existence with one another. There will always be naysayers in every walk of life that will hate as a matter of principle (one of the unfortunate consequences of free will), but eventually everyone will figure out in his or her own way that Love is the guiding principle and action that makes life worth living. Love is the only thing in this world that isn’t an illusion (or maya as Mr. Harrison might say). It’s been said before and bears repeating: when Allen Ginsberg was asked on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is love all you need? The bard replied “I would say awareness is all you need. And that love stems from awareness.” And allowing Derek Taylor the last word: “They still represent the 20th century’s greatest romance.” Amen.