Raider of the Lost Arts

Complexity

In the beginning, there was monophony.

Basically just a bunch of monks moaning in monasteries. Oh, there were many other sacred and secular musical forms developing in other cultures before and during, but there’s next to no documentation of it. Not like the European church music of centuries ago. Ascetic monks make fastidious clerics.

Then they realized––probably from the polyphonic instruments of the keyboard and string variety simultaneously emerging––that they could have different persons or groups sing different notes to form chords, and choral singing was born. Modern theory developed concomitantly, with the 12 notes of the western system having fallen into place and C major/Ionian having become the center of the diatonic universe.

(Meanwhile, over in Tibet, a different ilk of monk was hashing out the details of another kind of singing involving overtones and generally just pushing the limits of what the human voice could do. In India, it was microtones, odd time signatures, and improvisation.)

Bowed string instruments were capable of what the voice wasn’t: resounding indefinitely, and their inclusion in various ensemble permutations increased over time and eventually led to the rise of the orchestra. The same also goes for the instrumental companion to the Christian choir––the organ, which slowly developed to involve not only a player’s ten fingers but also their feet in the production of tones in multiple octaves, which essentially turned a single performer into an orchestra.

The music that was subsequently composed for these instruments started simple and expanded from there. The Renaissance gave way to the baroque, the classical to the romantic, until finally the 20th century blew the roof off of what was previously possible. Upper harmony and limit-stretching experimentation were the mortar in the classical and jazz mansions, with the serial 12-tone system coming to being in the former, and 7th, 9th 11th, 13th, and wild new passing chords developing in the latter, with substantial cross-pollination. All of it served to convey a wider, subtler range of emotions, and still stands as a monument to everything good that is possible through complexity in composition.

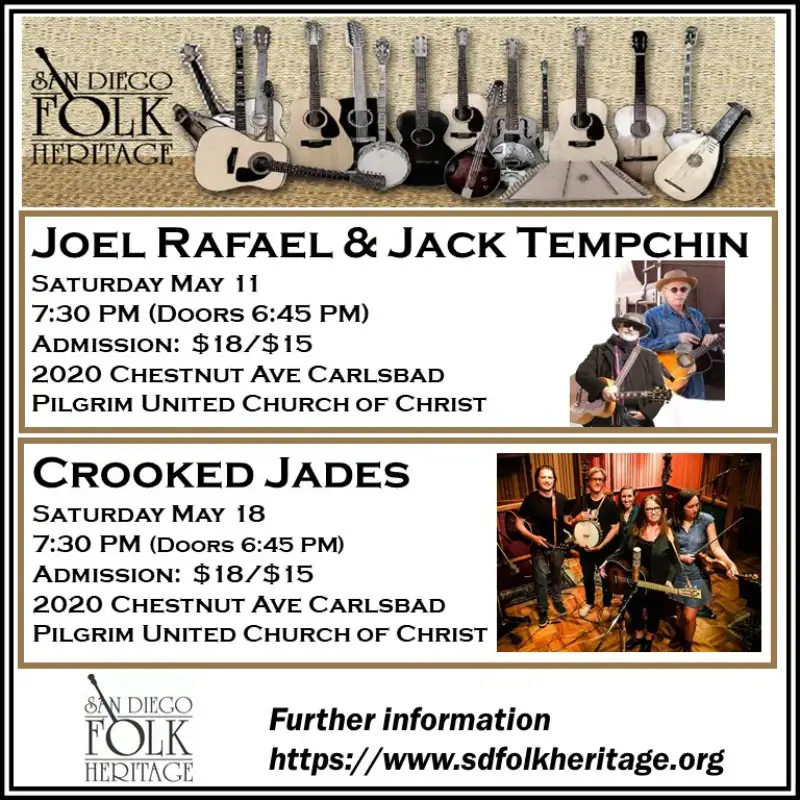

Secular folk music resisted evolution; it was the people’s entertainment played by austere commoners on relatively inexpensive, highly versatile and portable instruments like acoustic nylon and steel string guitars, banjo, dulcimer, lute, mandolin, and the “fiddle,” which was just classical music’s coöpted violin played in a new, less precise way. Other countries and cultures had different but analogous variations of these instruments and styles in their quiver (Spain: flamenco, etc.) but the results were generally the same: folk music bonded the community in song and dance, appealing to the widest common denominator in its relative simplicity and indigenous specificity.

Jim Crow and gospel begat blues, which in turn begat jazz, but blues was also utilized to craft new proletariat genres in the early- to mid-20th century: pop, rock and roll, and R&B. All three idioms were aided and abetted by accessibility of form and the invention and evolution of recording and broadcasting technologies, both of which now fostered the potential of bringing distantly generated music directly to most people’s living rooms.

You could hear Frank Sinatra, Mel Torme, Dean Martin, and Nat King Cole coming through the den radio during the wars, along with any one of a number of velvet-voiced chanteuses (Billie Holliday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Julie London, etc.). There is a subtle sophistication to this particular body of popular work, a deft blending of jazz’s high-falutin aspirations and instrumentation with catchy pop melodies that were the spoonful of sugar to the complexity’s medicine. These combined aspects have enabled this music to more than stand the test of time.

Rock ‘n’ roll pawned sophistication for surreptitiously salacious vibrancy. The post-war invention of the “teenager” called for entertainment that equated music with the new disposable-time-and-income courtship rituals and barely concealed sex happening in cars at public make-out destinations across the US. From the Caucasian-shunning juke joints of the South came the answer; the raucous, visceral music of the “Midnight Ramble,” where all the hair was let down and everything short of coitus happened on the dance floor. Chitlin circuit performers like Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, and Fats Domino cranked out high octane, low-brow dance tunes with thinly veiled references to sex that could still pass the scrutiny of radio censors. The blues realm had road warriors galore, with the Kings (B.B. and Freddie) and Muddy Waters taking their cues from Robert Johnson and Son House and passing the baton to the likes of John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, and Jimi Hendrix, who brought some of jazz’s complexities with him to the psychedelic, blues-based Experience.

And then white folks got a hold of it, sucked most of the soul out of it, and pop was born. Elvis Presley wasn’t the first teen idol (Sinatra had soiled the knickers of bored, co-ed-deprived young women during World War II), but he perfected the archetype. Elvis swung and shot from the hip and the gut, and although the Sun output is historic gold, this was the beginning of a periodic trend where roughly every ten years the music of the masses would be dumbed down to simple but exciting songs the youngsters could call their own. From this point on, kids were consistently led away from more intellectually stimulating work by the pied pipers of pop.

The Beatles were an astonishing anomaly to this trend in that they started out as a youth fad and got more complex as they went along. In the midst of the golden ages of both jazz and Motown, they were the first “boy band,” with all four of them having the same stature and adolescent focus as an Elvis in their own right, and with their music tailored almost exclusively to teenage girls. But from the get-go they began dropping subtle bits of sophistication into their songs; whether it was “She Loves You”s chorus vocal harmony ending with George Harrison singing the sixth, putting him a close major second interval over John, not dissimilar to a barbershop a cappella or the augmented passing chords dropped sparingly but effectively into early singles like “From Me to You” and “All My Loving,” or the 7th chords and upward key modulation of “And I Love Her,” they all but singlehandedly brought accessible innovations back into the pop music vernacular.

By the mid-late sixties they had dispensed with the foot-in-the-door bubblegum pretenses and had embraced the Avant Garde, with songs like “Tomorrow Never Knows”––despite only having two chords––emulating musique concrete in its use of multiple tape loops over a strange but wildly compelling new beat from Ringo Starr, and adjacent to a Tibetan-book-of-the-dead-derived lyric sung by John through a rotating Leslie speaker. George Harrison’s “Within You Without You” from Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band continued the pop world’s nascent acquaintance with Indian music (Revolver’s “Love You To” had kicked off that party), replete with exotic harmony and melody, and galvanizing rhythmic modulations that were heretofore unprecedented on such a widespread commercial scale.

John might have been the “coolest” Beatle, but though there’s something to be said for his instinctive time signature changes in cuts like “I’m Only Sleeping” and “She Said She Said,” Paul was responsible for most of the complexity in their music. Whether it was the aforementioned use of tape loops or simply what he did for the bass guitar in terms of elevating its profile without being overbearing, Paul was the bowsprit of that pioneering vessel.

Even the Beatles had their influences, and Bob Dylan is near––if not at––the top of the list. It was Dylan’s lyrical sophistication that catalyzed the Beatles’ shift from sappy teen pop to more grown-up themes and words. After Dylan, poetic prodigiousness became all but compulsory (though most lyricists stuck to three verses), and a handful of artists followed suit, including Joni Mitchell and her vast, jazz-esque alternate-tuning chord vocabulary that matched her voice and words.

Many subsequent bands took the innovations and ran, adding ells to the pop estate the Beatles had built. One of the most noteworthy to take up the torch of progress was Yes, who combined their jazz, classical, country, and rock stew with prodigious instrumental and vocal chops––and a couple of hat-tip Beatles covers––to create insanely innovative yet still profoundly moving music. Led Zeppelin morphed the blues and acoustic folk-rock into something much more epically orchestrated and strove for an almost jazz-like improvisational approach in the live milieu. Pink Floyd transformed their psychedelic blues-rock into lavishly arranged, album-oriented pop gold with the diamond-plus-selling Dark Side of the Moon, and subsequently Wish You Were Here. Groups like Genesis, Queen, Rush, ELP, King Crimson, and even straight pop geniuses like David Bowie, Billy Joel, ELO, and Elton John struck a sublime balance in their harmonically sophisticated yet highly listenable music.

From the late ’60s to the mid ’70s, commercial music was by and large a lavish feast for the ears. Then another dumbing-down phase kicked in with the rise of punk in 1976 England. Economic turmoil and social disenfranchisement sparked an exhilarating youth movement that rejected everything overwrought and opulent in the contemporary culture and politics by which average denizens felt oppressed. It was music anyone could make, a proletariat art form, and, for a short while, music was handed back to the working-class masses on a silver record platter.

From then on, complexity had to start looking for other outlets, mostly in the realms of production and orchestration. New wave had clever heroes in the Police, XTC, the Cars, and so many others; rock, heavy metal, and thrash had Van Halen, Iron Maiden, and Metallica; R&B had Earth, Wind, and Fire, Stevie Wonder, the Commodores, and more who employed upper harmony chords and upward modulations; the jazz-fusion world teemed with technicians and deft composers as always; and the grunge era produced Primus, Tool, Helmet, the Jesus Lizard, and Soundgarden.

1997 may not have been the year sophistication actually died, but that was certainly when it got its terminal diagnosis. It was the beginning of the ascendancy of Britney Spears, Hanson, the Spice Girls, and boy bands like Backstreet Boys and N’Sync, coddling a newly emerging generation with shallow fluff. Autotune was introduced that year, which meant the latest up-and-coming singers could skip the talent and practice and could now be chosen purely for their looks to be groomed for stardom. Even some veterans got on board the Autotune train, with Cher becoming one of the first to be associated with its aurally dehumanizing robotic effects. Now, because it’s become standard practice, even amazing singers get Autotuned.

As with most movie studios, and especially post-Napster, the major labels stopped taking risks and started opting for ringers who could deliver from the onset. The music––and the artist––had to hold our ever-wandering attention or everyone involved would lose what little money there was to make. Pop, already obeying all the rules, got long-term reduced to its lowest common denominator; no matter what the genre, everything started getting rhythmically and tonally quantized on a slow but steady regression back to disco, with fake rhythm sections providing an all too perfect bedrock for singers to offhandedly recite inane lyrics about dancing to one’s favorite song and drinking champagne in the VIP section of some club they never get around to naming.

Independently produced music seems to have taken a parallel, collaterally damaged dip, with fewer artists receiving much of an education before releasing work heavy on layered production and atmospherics and light on variety and harmonic depth (some truths never get old; those same three chords, though…). Lyrics have become too sparse and personal, frivolously sung in too blasé a way to connect with anyone beyond an exclusive inner circle (the artist’s generation, basically).

Meanwhile, the classical music genre is all but dead on the vine. This was true even pre-COVID, as concert and recital audiences and album sales were already dwindling. Jazz is chugging along, but it’s ossified now, no longer the fresh new face in town. Music with any complexity in it has been subsisting in separate, underground niche bunkers for years, like James Cole in 12 Monkeys, replete with backwards temporal wanderings, trying vainly to find what was lost and fix what was broken.

Crisis eras leave no headroom for intellectually challenging art. Everyone hunkers down and sticks to what’s safe when the fit hits the shan (or is about to). But if there’s anything we’ve learned, it’s that these things cycle in phases depending on the state of our society in a given era. Now’s not the time for fancy frills. But once the smoke clears…look out for a sonic revolution.

The most complex pop song of all time! https://youtu.be/ZnRxTW8GxT8