Yesterday And Today

Between Fact and Friction: Hanging Out in the Ozone with HARRY SMITH

ART: the conscious use of skill and creative imagination acquired by experience, study, or observation.

I think that it’s important that people be aware of some of the creative ways in which some of their fellow men are deviating from the norm. Because, in some instances, they may find these deviations inspiring, and might suggest further deviations, which might cause “progress.”

– Frank Zappa (1940—1993)

Avant-garde is French for bullshit.

– John Lennon (1940—1980)

Whether a master, an apprentice, or a dilettante, on some level of reality, every one of us is capable of being an artist, and anything can be a medium for artistic expression, be it the garden, the workshop, the kitchen, the studio–anything. We are all creative beings, and to be an artist is to be on a perpetual vision quest and to summon the ultimate expression of what we find to be true within our Self.

There is an idea floating around, suggesting that if you can copy a master, you can become a master. That principle may be true regarding truck driving or brain surgery, but to become a consummate visual or performance artist there is still a mystical x-factor at play when transforming your skills and vision from that of a mere impersonator into a genuine innovator.

“Progress is not possible without deviation [from the norm],” as Frank Zappa famously pointed out at the end of the ’60s, and it requires an enormous amount of courage (and sometimes ignorance) to express any truth that stands in opposition to the accepted mores of your own epoch. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788—1860): “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

So, what does it take to be an innovator in the world today? That is a fairly radical idea in the face of our current culture, where it has been relatively easy to confound the masses into accepting the post-modern haste of crass consumerism. And, as a pulpit for preaching values (false or otherwise) to the congregation, there has never been a more powerful tool for manipulating consciousness than the mass media. It’s a barely perceptible line between education and propaganda when it comes to toying with human psychology–just ask Edward Bernays or Stanley Milgram how easy it is to get the herd to go along with an idea, no matter how noble or nefarious that idea may be.

The same thing could be posited regarding the avant-garde and the art world–why are we attracted to a piece of art? Does our psyche/soul respond to something that is celestial, eternal, and transcendent? Or, do we respond to a certain type of stimulus because we’ve been conditioned and told how to respond to it? This is the dance of the intelligentsia upon our crania. Much as we’ve been educated and told of the importance of art throughout the ages, there are some that would pragmatically assert that the entire modern art world is a schuck, a hussle, a dodge: in short, a creative public relations flimflam.

There is a point where we can be so collectively hypnotized by an idea that it turns into a belief system (b.s. for short), and then that belief calcifies into dogma, and the next thing you know we’re no longer capable of entertaining a new idea or concept because we’ve stagnated into intellectual entropy.

This sort of malaise flies completely in the face of what we conventionally refer to as the avant-garde: that attempt to apply meaning or significance to anything in society or the art world that is thought to be experimental, radical, or unorthodox. “Art” is, of course, a part of our culture, but that same culture can often be a clutter of mass-produced crap (thank you for pointing that out, Walter Benjamin [1892—1940]), intended by design to dazzle, daze, and dislodge you from the moorings of your inner compass. In a world of relativity, “truth” becomes a moveable feast, and in order for us to evolve as a species we’d all be well advised to cook up something innovatively transcendent in this eternal Now, rather than munch upon the moldy figs of yesterday’s constructs.

Much of what we call evolution is merely taking a pre-existing norm and giving it a slight tweak, or rearranging a series of familiar objects into a new pattern of resonance. If “one man gathers what another man spills,” to quote the relativity of Robert Hunter, then call the gathering of society’s detritus what you will–be it archiving or collecting trash, and if there were ever a “St. Stephen” of the 20th-century avant-garde, it would have to be Harry Smith.

*****************

Through the deliberate manipulation of his reputation through unabashed self-promotion and an occasional outright deception, the life and work of Harry Everett Smith (1923—1991) remains an enigma of immense proportions, and he’s definitely one of the more provocative creatures of 20th-century culture. Smith was a radical cross-pollinator within the disciplines of filmmaking, painting, anthropology, and archiving. And much ink has been spilt in the attempt to explain his innovations and significance within the expanding parameters of western art and thought.Poised somewhere between the Fool and the Hierophant in the Major Arcana of the Tarot, Smith was a Self-selected Magician primarily cast into the lifestyle of a Hermit. As a practicing occultist, he certainly cast a spell over the art world, producing multiple interpretations and debates of his significance.I prefer to think of Smith as a divination anthropologist, a magical manifestor, an alchemical artiste, and a compulsive collector of objects. As a filmmaker and painter, he turned the avant-garde world on its head in the 1940s and ’50s with his unique and genre-busting abstract films–they’re nearly impossible to describe, although many academicians have attempted to place his output on the Freudian couch of analysis. All we can do as spectators is speculate about what Harry Smith’s work adds up to, and, ultimately, all we really end up with is a meditation on our own projections, fantasies, and value systems.For some, every moment is an act of faith, and Smith stood in diametric (pentagrammic?) opposition to all faith-based dogmas by exercising his extreme will as a practicing initiate of the Ordo Templi Orientis (“Order of the Temple of the East” or “Order of Oriental Templars”), the magikal organization led by Aleister Crowley from 1925 until his death in 1947. Under Crowley’s tutelage, the O.T.O. shifted toward the philosophy of Thelema, whose most famous maxim remains: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Love is the law, love under will.” You can find “Do what thou wilt” scratched into the run-out groove of initial pressings of Led Zeppelin III.

You can also find that quotation included in the booklet for the Anthology of American Folk Music, the objet d’art that Smith is perhaps most famous for. The booklet also includes this quote from Rudolph Steiner: “The in-breathing becomes thought, and the out-breathing becomes the will manifestation of thought.” Smith compiled and edited a trio of double LPs from his vast collection of 78 rpm recordings in 1952 at the behest of Moses Asch, the owner of Folkways Records. (There will be an entire essay dedicated to this landmark collection of recordings in part two of this feature in the April edition of the San Diego Troubadour.) One contemporary writer has suggested that an entire cult has sprung up around a personage that was essentially just a “collector,” but that P.O.V. regarding Smith and the Anthology is analogous to suggesting that Picasso was merely a collector of paint tubes. Like the Old Masters of any artistic renaissance, the genius lies in the synthesis of discreet objects and symbols, and imbuing them with a radical reinterpretation through placement and juxtaposition. This is something that Smith did time and again in his experimental films, and that is certainly true of the performances that are documented on the Anthology of American Folk Music. Like most of Smith’s output, the Anthology can be thought of as an alchemical text, with each volume representing the four directions and the four primary elements of life: earth, air, fire, and water. The earth-themed volume of the Anthology was curated by Smith in 1952, but remained unissued until 2000.

Drawn from 84 recordings made during the period of 1927—1932, and without bothering to deal with any proper legal clearances, there is no way to overemphasize the significance of Smith’s pirated mix-tape. It single-handedly sparked the folk music revival of the 1950s and ’60s, and its reverberations continue to be felt by every single person who has ever picked up an autoharp, dulcimer, banjo, guitar, or harmonica. The oft-quoted Dave Van Ronk (1936—2002) places the Anthology into pristine historical context: “That set became our bible. It was an incredible compendium of American traditional music, all performed in the traditional styles. That was very important for my generation, especially those of us I consider ‘neo-ethnics,’ because we were trying not only to sing traditional songs but also to assimilate the styles of the rural players. Without the Harry Smith Anthology we could not have existed, because there was no other way for us to get hold of that material.”

*****************

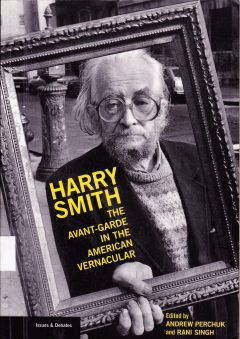

The biographical sketches that do exist of Harry Smith read much like a Paul Bunyan/Johnny Appleseed folk tale, and it is frequently difficult to know where the fabrications end and the truth begins. To draw your own conclusions you are directed toward Think of the Self Speaking: Harry Smith–Selected Interviews, and Harry Smith: The Avant-Garde in the American Vernacular, both edited by the tirelessly devoted Rani Singh, who is in charge of the Harry Smith Archives, housed at the Getty Institute.

It is a fact that Smith was born on May 29, 1923, in Portland, Oregon, and that he spent his formative years in Washington state, between Seattle and Bellingham. His father, Robert James Smith, was a fisherman and watchman employed by the Pacific American Fishery, a salmon canning company. Smith’s paternal great-grandfather, John Corson Smith, was a Union colonel in the American Civil War, and served from 1885—89 as Lieutenant Governor of the state of Illinois. He was also a prominent Knights Templar Freemason, authoring several books about the history of the order.

Harry Smith had a peculiar relationship with his mother that bordered on the Oedipal, occasionally claiming that she was the Romanov Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia (and/or that he was the orphan of Aleister Crowley!). In reality, Mary Louise Hammond was born in Sioux City, Iowa, and descended from a long line of schoolteachers. She taught on the Lummi Indian Reservation from 1925 to 1932. Smith’s parents were Theosophists and both were passionate about folk music.

Speaking to P. Adams Sitney in 1965 for Film Culture magazine, Smith attempts to shed some light about how his worldview was shaped: “When I was a child, there were a great number of books on occultism and alchemy always in the basement. My father gave me a blacksmith shop when I was maybe 12. He told me I should convert lead into gold. He had me build all these things, like models of the first Bell telephone, the original electric light bulb, and perform all sorts of historical experiments. I once discovered in the attic of our house all those illuminated documents with hands with eyes on them, all kinds of Masonic deals that belonged to my grandfather. My father said that I shouldn’t have seen them, and he burned them up immediately. That was the background for my interest in metaphysics and so forth. Very early my parents got me interested in projecting things.”

Smith studied art and photography throughout high school and wrote in his yearbook that he wanted to compose symphonic music. He managed to get a deferment from the draft due to a curvature of the spine, and during World War II he took a job as a mechanic working on Boeing bomber planes, using his spare cash to purchase blues and hillbilly records. Between 1942 and 1944 he studied anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle, until a chance visit to San Francisco redirected his life. After being introduced to marijuana at a Woody Guthrie concert, he dropped out of college, and adopted the habits of bohemia, mutating into a beatnik.

Like most of the movers and shakers of the Beat Generation, Smith became drawn to bebop and hung out in nightclubs where he could hear the sizzling improvisations of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. He began to paint a number of jazz-inspired murals and canvases (since destroyed), and started a decades-long process of creating avant-garde films by developing a technique where he painted directly upon the film stock, to be accompanied by live performances of bebop music when they were screened.

A Guggenheim grant in 1950 allowed the completion of one of his films, which in turn provided him with the funds to move to New York City, so that he could “study the Kabbalah and hear Thelonious Monk play.” When his grant money ran out, he attempted to sell his record collection to Moses Asch at Folkways, who in turn challenged Smith to transform his stack of 78s into an anthology of folk music for the brand new 33-1/3 rpm format. That compilation changed the course of music history.

*****************

Smith got involved with a few recording projects in later years: he produced the Fugs debut in 1965 (The Village Fugs Sing Ballads of Contemporary Protest, Point of Views, and General Dissatisfaction); Allen Ginsberg’s First Blues: Rags, Ballads and Harmonium Songs (recorded at the Chelsea Hotel in 1973, released in 1981); and a three-LP set titled The Kiowa Peyote Meeting in 1973. Otherwise, he primarily devoted the rest of his life to the creation of his experimental abstractions of celluloid, demonstrating how he was a visionary master of drawing down symbols from the astral plane.

Every project that Harry Smith embarked upon could be considered a form of divination, and he practiced his own kind of esoteric magik that does not reveal itself easily to the perceiver. If you take the Anthology of American Folk Music as a collage of found objects, it is easy to dig how much Smith could interpret phonograph records as occult symbols. Because when they are experienced in the proper spirit, phonograph records provide a very special form of time travel, capable of transcending the third dimension.

Smith once stated that his films should be watched in sequence or “not at all.” He preferred not to title his works, giving most of his projects a number instead of a name (No. 1 through No. 20). His best-known work, Film #12 (aka Heaven and Earth Magic, the title from Jonas Mekas), looks like a prototype for Terry Gilliam’s early animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus (circa ’69—’74). Film No. 18: Mahagonny (Smith: “A mathematical analysis of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass, expressed in terms of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny”) was about as over the top as you could get in terms of presentation. It took Smith ten years to create, runs at two hours and 21 minutes, and requires four separate 16mm projectors onto a single screen, or onto two billiard tables suspended over a boxing ring, so it’s no small wonder that it rarely gets screened in public.

Smith seems to have settled down somewhat during the last three years of his life, where at the invitation of his friend and patron Allen Ginsberg he became the “Shaman in Residence” at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, founded by Tibetan meditation master and teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

At Naropa, Smith taught classes on alchemy, Native American cosmologies, and the rationality of namelessness. He returned to New York City in early 1991 to accept a Chairman’s Merit Award from the Grammy Foundation, and before he could return to Naropa, Smith suffered a bleeding ulcer followed by cardiac arrest at the Hotel Chelsea in Room 328. His friend, poet Paola Igliori, described him as dying in her arms, “singing as he drifted away.” An hour later, Smith was pronounced dead at St. Vincent’s Hospital on November 27, 1991.

In 1986, Smith was consecrated a bishop in New York in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, which claims William Blake and Giordano Bruno in its pantheon of saints. After his death, Smith’s branch of the Ordo Templi Orientis performed a Gnostic Mass in his honor at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village.

Harry Smith no doubt pushed the absolute boundaries of tolerance in American society for what we usually term “eccentricity.” In fact, if it weren’t for the rich and/or powerful friends that stepped in to help him throughout his life, he most certainly would have been jailed or committed to a mental ward for his inability to play by society’s rules and conventions. The fact that Smith DID manage to escape incarceration is a testimony that he must have possessed some kind of magikal skills. However, his numerous references to being an alchemist must certainly have been symbolic, because if he really was an alchemist he wouldn’t have spent the majority of his life trying to hussle together the funds to pull off his artistic capers. This is where Smith’s shadow side often got the upper hand. As Richard Metzger notes: “Apparently Smith never met a drug he didn’t like and would take any pill, drink any drink, smoke any joint, or snort any powder offered him, and he was not at all averse to huffing gasoline, when that’s all that was around. For long periods of time he lived off the kindness of others and borrowed lots of money he had no intention of ever repaying. Yet Smith himself was said to be generous to a fault.”

If you look at the evidence of Harry Smith’s physical deterioration: his bleeding ulcer, the very few teeth remaining in his head, and an endless penchant for chemical derangement–it would appear that he struck a deal with the devil. And lost.

Unless we’re talking about the reward of immortality, because that is what phonograph records and literature and celluloid heroes are all about: they provide a form of divination and the means of placing your stamp upon eternity. On that score card of existence it seems that the enigma that is Harry Everett Smith is something that artisans, mystics, academics, and historians will be exploring, and debating, until the end of time. Wherever his eternal soul is hanging out these days, the reality of Harry Smith’s life and artistic output will remain alive in the hearts and minds of the people on planet Earth as long as there is a race of beings intact to ponder such things.

There’s way more to say about Harry Smith, so stay tuned for Part Two in the April edition of the San Diego Troubadour!